I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the role of a certain mountain in my life.

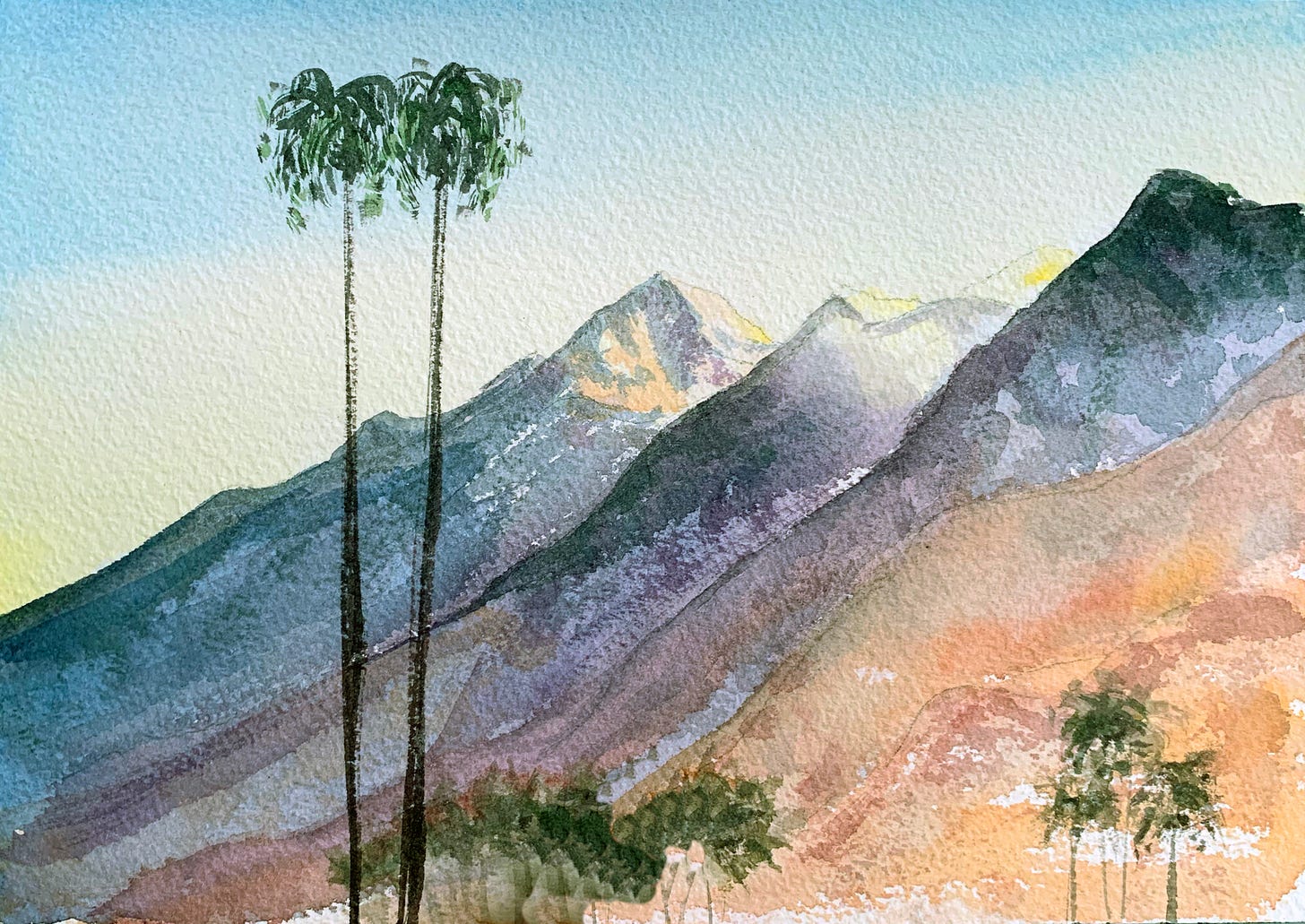

Funny, isn’t it, returning to a landscape from one’s childhood and finding it still fully charged with power and deep sense-memories. Mt. San Jacinto, rising so abruptly from the California desert, affected me strongly as a child growing up in its shadow. Returning as an adult for a visit, I find that it continues to cast its spell on me.

The mountain marks not just a physical place, Palm Springs, but a spatial reference point for my inner being. Its sheer verticality, its gigantic presence, seeming to rise straight up into the bright blue sky, has been the “north star” of my orientation since I arrived in the desert at age seven. All the activities of daily life take place in front of it, or on it, or in its purple shade when the winter sun sets behind it at 3:30 p.m. Growing up, my bed was always placed with the headboard toward the mountain (my choice). In dreaming, the mountain always had my back.

The mountain marks not just a physical place, Palm Springs, but a spatial reference point for my inner being.

Awareness of the mountain has been fundamental to my spatial orientation, my sense of movement, and sense of well-being. If I could see or sense the mountain, I knew where I was. Mt. San Jacinto set the cardinal directions for me: west was clear, because LA and my grandparents were on its other side. I figured the other directions out from there.

With its fierce frontal force, the mountain also created a strong if unconscious experience of planes of space: it’s always right before me, or right behind me as I face east to the morning sun and the horizontal spaces of the widening Coachella Valley. The spaciousness imprinted within me, helping form an inner map of vertical and horizontal, west and east, north and south, up and down.

I was not aware of these forces as a child, of course. But as a 20-year-old dance student, in New York City one summer, I gigged as a research subject for a study at NYU about the spatial orientation of dancers. It was such fun, I remember, to guess precise horizontal or exact vertical when placed in a black box, and the sorting of shapes and directions were easy games for me. After three days, I happily picked up my check for $75 and was told that my scores were so highly accurate that they set the high end of the spectrum for the study.

Now, what is spatial orientation, what’s the relationship to movement, and how did I seem to have a knack for it? I began to study the science of the movement senses as I observed my own.

I noticed an ease with directions, with reading a map, getting around in nature and in town, and locomoting in the dance studio or on stage. I had a kind of “sense map” of the spaces around me. Thinking back, I realize that my formative spaces were not the suburban neighborhoods of West Hollywood, but rather those childhood landmarks of the desert mountain.

In mid-November of this year, I returned to Palm Springs for a family visit. The mountain once again worked its influence on me, clarifying my sense of space, time, and grounding. As I revisited my childhood neighborhoods—eight homes over seven years—I noticed anew how they each orient to the mountain.

Our First Home at The Tennis Club

In February, 1960, a taxi from LA (another story) delivered us to the Palm Springs Tennis Club. It was a very posh place, and we were anything but. My dad was the drummer in the band at the night club there. The manager, future Palm Springs mayor Frank Bogert, gave us a pretty bungalow on the grassy grounds for a week or so while our family got housing sorted. My little sister and I had the run of the place, and spent much of the time exploring the iconic pool, the rocky slopes of the mountain’s base, and the restaurant built right into it.

A favorite story was that one night, during a set, a mountain lion came down from the mountain and sat at one of the windows, looking in while the band played on.

We came down to earth staying at a dusty motel down valley for a few weeks, then moved back under the mountain to a neighborhood of tiny homes across from The Mesa (now condos). I started school again, third grade.

The Canyon at Windy Point

A few years (and homes) later we moved to a new subdivision in Blaisdell Canyon on the north side of the mountain. It was remote from town, but the rent on Sunnyslope Lane was cheap. It was windy as hell, icy cold in winter, and hazardous for vehicles, especially the school bus. With few close neighbors, it was a good place for my dad to play jazz records as loud as possible and bang on his drums.

My sister and I played in the wide open stretches of desert, riding our bikes in and out of wind flurries and dust devils until the sun set, early, behind the mountain. There was no cable service, so no TV, but we didn’t miss it. I was 11, and my sister was six.

Family fortune improved and we moved back into town, to a very nice area of homes that were walking distance to the junior high. We had air conditioning for the first and only time, and our neighbors had pools! Our front door faced the mountain. It was perfect.

Then we moved again, deep into Native American lands.

The Bus Stop and the Ranch

This corner, facing the imposing Mt. San Jacinto, was the school bus stop for my sister and me the last year we lived in Palm Springs. In recent years, she and I have been reconstructing the puzzle of our memories from that time, growing up in the resort during the actual era of “mid-century modernism.”

The bus stop marks several pieces of the puzzle with strong personal memories: a flood, and two rescues.

In 1965, we were 13 and eight. We lived in a rustic tenant’s house on a lone, small ranch at the end of a long dirt road named Bogert Trail (named for Frank Bogert). It was located up a mountain canyon, on land of the Agua Caliente Indians. Now dubbed Andreas Hills, it’s still Native American land, but these days it’s full of multi-million-dollar gated estates.

The house on the ranch had huge windows facing the mountain, with great sweeping views due to the site’s elevation. We shot arrows into cacti with our dad, and played in the ravine behind the ranch and the wide wash in front of it. We explored the horse corrals and, careful to avoid snakes, scorpions and coyotes, roamed the lemon grove amid the fragrance of creosote and challah baked by our mom.

The bus stop was a couple of miles down the road near the south end of the main drag, Palm Canyon Drive. We remember waiting here for the bus in the sparkling mornings, or for our dad to pick us up in the afternoons in his blue Austin Healy Sprite for the dusty drive up the hill.

In the fall, just before Thanksgiving, clouds covered the mountain top and the skies opened, pouring rain. Canyons flash flooded. With so much rain, the washes ran full and true to their name, washed out the roads in town. My sister was dropped off after school at the bus stop as usual, but our dad’s low-slung sports car couldn’t cross the raging waters of the wash to get her, so a horse and rider set off from the ranch to carry her safely home.

My rescue was less dramatic, outwardly. The flood caused the next days at school to be cancelled, which meant I was saved from singing Rock of Ages, solo, in front of the entire junior high school in the Thanksgiving assembly.

I gave silent thanks for my deliverance over those next few days, watching out the windows as the light changed on the mountain’s face and the skies slowly cleared.

Returns

Although we moved back to LA the next year, Mt. San Jacinto has remained a central orientation point for me, wherever I live. When I return, I peer out the window of the plane as it prepares to land, craning for the first view of its sheer face. If I’m driving in, my heart beats faster as I round Windy Point and I accelerate past Overture Drive, opening my windows for the first whiff of creosote. Driving through town, I nod fondly towards The Tennis Club and hope for an occasion to visit its iconic restaurant, Spencer’s, and to clamber around the rocks once again. Then my heart slows as I approach Indian Canyons, home once again, for a few days anyway.

When I leave, I notice my movement is more clear. I’m firmly oriented to the sun, the mountain, the sand, the canyons, the hidden waterways. My eyes are refreshed from gazing far and wide, softening and then sharpening focus. My hearing is calmed from the soughing of wind in the smoke trees and the palms and the calls of the desert birds. My footfalls are more secure, having hiked across the open sands once again, even for just a short while.

Do you have a natural landmark that orients you? I’d love to hear about it.

From our archives, more about the movement senses:

Lovely writing, Valerie! Another one of your many talents!

It makes me think of the phrase “stomping ground” and how an intimate familiarity can inspire, a quality of place that perhaps only nature can do? The balance between knowing a place but also being able to be changed by it decades later is a true marvel. The Romance languages have two verb forms of ‘to know’: ‘to know of’ and ‘to know personally.’ The beautiful way you present the dynamic relationship we can have to our spaces makes me want to live life more fully!