Movement For Balance

Not a still point of perfection, balance is a dynamic activity at every age

Years ago I began to study the role of movement in preventing falls in the elderly. After leading movement experiences in Stanford University’s dSchool project, Design for Agile Aging, and using its Design Thinking methodology, I choreographed and adapted new exercises to enhance mobility for myself and others. This Agile Aging approach has enlivened elders via a Mondays in Motion video program and in activity classes from California to Florida, most recently at Eskaton communities in Sacramento (with valuable assistance from neurodiverse students from Meristem.)

Understanding the three aspects of balance has been a cornerstone of these beneficial exercises.

Balance Integrates and Disintegrates at Either End of Life

Our balance develops in early childhood as we learn to focus our eyes, control our head movements, roll, stand, and walk. Very early and throughout life, righting reflexes help to respond to rapid loss of balance and assist with integrated movements of the head on the body’s trunk.

In our older years, however, our balance is less secure. It’s not a matter of strength, energy, or will. While we may have heard about reflex integration or “sensory integration” during the first years of a child’s life, in our later years reflex and sensory dis-integration occurs. We may not really notice this gradual change until we lose our balance and fall. This happened even to me, once very early in a dark morning getting ready to fly to another city to lead a fall prevention workshop: I tripped over our sleeping dog, fell against the wall, spilled the cup of coffee I was carrying, and scraped up my arm dramatically enough to have an exhibit A at the workshop. (Note to self: turn up the lights when it’s dark.)

Balance doesn’t have a center spot; it’s rather the nexus of an intricate interplay of dynamic forces. The result is balance.

Have you ever taken an unexpected tumble? I’m curious to hear your stories.

Balance as a Movement Activity, Not a Still Point

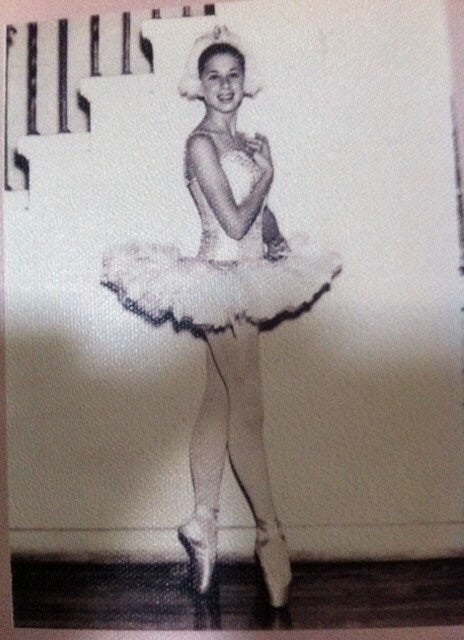

As a young ballet dancer, striving and often struggling in sustained balances especially on pointe, I was told by my teachers that the key to balance was to “find my center and hold it.” Huh? I looked around at other dancers who seemed to be doing just that, and pondered how they were finding “center” and how they were “holding” it. Later in my dancing life, I realized that this was terrible advice, counter-productive, and just plain wrong.

Balance doesn’t have a center spot; it’s rather the nexus of an intricate interplay of dynamic forces. The result is balance. Trying to “hold it” is a misguided and outdated concept of gripping, moving towards the body’s center; balance is not a still point of perfection, but rather an ongoing activity of micro movements of the spaces of the body. (Dance teachers, please take note! Helpful imagery can be found in Eric Franklin’s work, Franklin Method.)

Observe Balance for Yourself

Try this. Stand comfortably near a sturdy chair or wall (in case you need some support) with your feet together. Close your eyes.

Observe your “balance.” Is it a still point of perfection? Probably not. I suspect your balance is a more active experience, one of small and subtle shifts; of moving this way, then that way, never coming to a still-point. Right?

You just experienced your own righting reflex, adjusting to your own movements.

The Three Aspects of Balance

Using Movement To Improve Our Balance

We can strengthen our balance by challenging each one of the three body systems in turn - vision, head alignment, and expansion of our personal space - by isolating each to function without the support of the others, and then moving with them as a whole.

For example, in the Agile Aging exercise Rainbow Wobblies we stand on one foot (unbalancing our usual stance), “spread our wings” (expanding ourselves spatially) and carefully and intentionally wobble on our standing foot and ankle. Our eyes are holding onto our balance for us. Then, we free our head and gaze to “follow the arc of the rainbow overhead”, challenging our spatial and vision system to pick up the slack as the vestibular (balance) system of the inner ear (the “carpenter’s level” mentioned in the video) is de-stabilized with the head movement.

Movement by movement, we can shift from excluding one and then another of these three systems. In this manner, we strengthen our balance by isolating the different body systems that contribute to stability, then integrating them again, over and over. Reflex and sensory integration, helping the body organize its many different senses, is not just for the very young.

Using Space to Help our Balance

Balance is also a spatial activity. We can expand our range of balance by exploring the spaces around our body, beginning with experiencing gravity and her playmate levity or lightness. Here are a few examples of combining eye exercises with gravity and levity play as well as range of motion.

A simple “stretch in bed” every morning is valuable to awaken our inner spaces and reconnect our sleepy muscles with our bones before standing. This most basic full-body yawn is the best exercise you can do before you get up in the morning (or even at night). Babies and animals do it naturally (my dog Dutch and cat Maisie are prime examples) and so should we.

Activities that involve expansion and contraction (as in a natural full body yawn) can also offer pathways to an heightened sense of one’s physical and spatial self. Similarly, doing an activity with a partner (cooking, dancing, gardening) can give one the experience of moving out into the world, or towards or with the partner, not only moving solo.

Moving fully through three planes of space by moving forwards/backwards, up/down, and side to side can also strengthen our movement integration and balance, at any age.

Helping the body organize its many different movement reflexes and senses is not just for the very young.

We can add easy and fulfilling exercises and activities in every day life by finding what invites us, what are we drawn to do? When my little granddaughter goes to the local playground, she is drawn to the swings every time. At 18 months, her eyes are busy learning to reflexively focus near and far (other children to see!) within the rhythmic motion of the swing. For myself, walking outdoors with my elbows freely swinging deepens my breath and allows my gaze to stretch similarly near and far. Neither feels like exercise yet do help expand our spaces, organize our vision, practice small righting movements of the head, and connect us with the movement forces that form and balance us.

For more, the movement approach of Spacial Dynamics® has many activities with which to explore these fundamental movements, with practitioners around the world.

More Agile Aging to Help Prevent Falls

Once we experience a fall, our fear of falling can itself cause falls. We can understand this if we notice that the gesture of fear is one of contraction. We don’t want to fall again so we move less and move with smaller steps, a wider gait, and with a smaller personal space. The antidote is clear: move more with fuller strides and fill the space around ourselves with … ourselves. Take up more space.

References:

An optimal state estimation model of sensory integration in human postural balance. Arthur D Kuo 2005 J. Neural Eng. 2 S235

Attention influences sensory integration for postural control in older adults. Mark S Redfern, J.Richard Jennings, Christopher Martin, Joseph M Furman. Gait & Posture – December 2001 (Vol. 14, Issue 3, Pages 211-216)

Franklin, Eric. Dance imagery for technique and performance. Human Kinetics, 1996.

Matthews, Paul. Space is Human.

Rose, Debra J. Fallproof. 2nd edition: Human Kinetics, 2010

That’s a great story! I’m glad you weren’t hurt, and could laugh it off. You are a fine role model for the little ones, showing that falls happen! Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for this informative and useful article, Valerie. It's been a perennial topic for me in talking with parents and other teachers about classroom behaviors that include fidgeting, leaving (or falling off of!) one's chair, and bumping into other students. The common plea from adults to "Just sit still!" is a command that requires practice and synchronization of multiple skills. It's a dynamic state, not a static one! For children who have not had the early developmental practice of integrating the three domains, challenges may get in the way of staying in one's seat, remaining still, and gauging the space around them. Particularly overlooked is the role of vision in developing a sense of spatial awareness-- I'm so glad you mentioned it. It is one of the detrimental effects of sitting infants in an upright position before they are able to maintain it independently.

We tend to celebrate benchmarks with an "earlier is better" attitude, but the impact of rushing some stages may not be apparent. I have worked with numerous children who were labelled "dyslexic" because they mixed up the direction of letter and number shapes. Each of them also exhibited immature balance/righting reflexes. When you think about the skills involved in quickly deciphering the direction/shape of abstract symbols (reading) is built directly upon the ability to master that directionality in one's own spatial realm. This is why Waldorf has early learners walk, skip, crawl the shapes of letters, form them with their own bodies, etc. before jumping into decoding text.

Fortunately, the brain is highly plastic, and remedial exercises like those you offer here (LOVE that your objects are so Waldorf-inspired!) can help to "rewire" the vestibular, ocular and proprioceptive systems in a stronger pattern. I have had the grace in my private school years to allow a student (labelled by his previous school as ADHD and "defiant") who continually fell out of his chair to just do his work on the floor, lying on his belly. Other preferred a rocking chair, a hanging swing chair, or a wobbly stool. Incorporating daily walks in nature is probably the best practice at any age: it offers ever-changing terrain underfoot and the opportunity to change our visual focus from near (where my next step will land) to far (the trail ahead, that beautiful horizon, is that a snake? etc.)

I'm noticing some young people I worked with in kindergarten experiencing a second awkward stage in high school as their physical bodies change dimension with every growth spurt. My aging mother is also experiencing frequent balance challenges as her posture stoops her over, changing her center of balance, her inner ear "level" and her range of vision. I will be making her a wool ball of her own and forwarding a link to your exercises. Thank you for sharing your wisdom and creativity!