Guest writer Kathy Fraser is a resource specialist who works with teens in a public school. With all children, particularly those who have special needs, she finds that rhythmic movement has been a powerful developmental tool. Kathy explains, and points to how adults can benefit too. - Valerie Baadh Garrett

As a teacher, I’m always watching for signs of learning difficulties and ways to address each students’ needs within the classroom in the most efficient way possible. Early in my career, I learned of certain therapeutic activities used in Waldorf curricula that support healthy development and also help treat academic and postural problems with patterned large motor skills.

A 3rd Grade class teacher at the Taiwan Waldorf School beings the day with rhythmic movement activity

Raised in the mistaken belief that the mind and body are distinct domains, I was fascinated to explore the connection between rhythmic movement and brain development. In my training, through remedial teachers at Rudolf Steiner College I discovered the work of Peter Blythe and Sally Goddard Blythe at the Institute for Neuro-Physiological Psychology in England. Their research on infant reflexes reveals a link between missed stages of movement and later complications with physical, emotional and behavioral development.

Here’s some of what I learned about movement development that is so relevant to my work today.

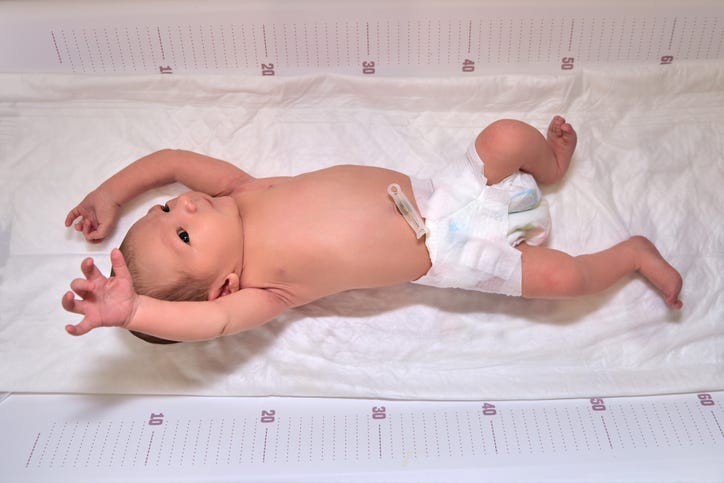

Babies all over the world move their tiny bodies in specific ways. While these movements are unconscious, they are far from random. There is a universal pattern every infant follows if conditions allow. Some of these reflexes begin in utero, others appear after birth.

The earliest reflex movements prepare the baby for its trip down the birth canal (in which it is an active participant), for breathing air, navigating in gravity, and generally getting adjusted to life outside the womb. Many of these reflexes aid the child in raising itself upright, creeping and crawling and eventually walking. Tied in with this is the development and integration of all the senses: touch, temperature, vision, sound, and a sense of the self in open space (proprioception).

Fully adapting to the “outside” world takes the brain/body two to three years, and requires lots of sensory stimulation. The role of the reflexes in this is critical: as each one appears and is practiced over weeks or months, the infant’s brain lays down the neural foundation for subsequent development and evolves into the next stage of movement. A weak foundation means the rest of the construction may be unstable. That instability can manifest in balance and coordination problems, difficulty with focus, anxiety, sensory processing or a number of other symptoms.

Read Movement and Learning by Valerie Baadh Garrett, here at The Movement Academy.

The Moro Reflex, one of the earliest to begin developing in the fetus, prepares the infant for its first “breath of life”. Premature babies delivered prior to 30 weeks will not have fully developed this reflex, which may account for a high incidence of lung complications among preemies. The reflex is activated in response to a surprising stimulus, like a loud noise: there is a sudden intake of oxygen (often followed by a cry), the arms are thrown up symmetrically with a quick opening of the hands and slight freeze before the limbs curl back in to a more protective position. The Moro Reflex normally integrates into the Adult Startle Reflex, in which the trigger causes a quick shoulder shrug and gasp, followed by a turn of the head to find the source. Once the disturbance is identified, we return to our previous activity or respond to the disruption.

If the Moro Reflex persists beyond the neonatal stage, the child may be extremely sensitive to all stimuli in the environment, unable to focus, and constantly “on alert”. This reflex is associated with the lowest brain stem area, the place we go when we “freeze up”. The primitive central nervous system cannot efficiently discriminate serious threats from mild ones, so the child may be in perpetual “fight or flight” mode. Because the Moro Reflex signals the body to increase heart rate and elevate adrenaline and cortisol, the child with a retained Moro may be very aggressive; conversely, he may be extremely withdrawn, silent, or immobile. This continual state of stress taxes the immune system, and the child may be prone to illness, allergies and infections. All these symptoms would certainly interfere with school life.

Normal development of the reflexes may be disrupted through trauma (including surgery), stress (particularly the mother’s), or injury. A lack of opportunity - not enough tummy time or crawling - may also interfere with reflex development.

When this happens, the body/brain continues to “practice” the movement. The most logical remedy then, is to give that movement plenty of time to continue its unfinished work. Much of this happens in the home, in conditions ripe for free movement, or in guided rhythmic patterns as advocated by the INPP, and others as well.

The late Swedish psychiatrist, Dr. Harald Blomberg, developed Blomberg Rhythmic Movement Training (BRMT), with precise, patterned repetition of these movements as needed on an individual basis. With older children and adults, the movements may be supplemented with isometric pressure.

We adults may have retained reflexes ourselves. In 2013, I attended a 3-day workshop on BRMT for preschoolers and kindergarteners conducted by Sheri Hoss, M.Ed., an education and movement specialist. Most of the participants were occupational therapists, two of us were teachers. We spent hours screening each other for retained reflexes and guiding each other through the remedial exercises recommended by Dr. Blomberg.

Our instructor emphasized remaining observant for signs of stress or difficulty and checking in with the test subject about their comfort level: some of the exercises may elicit emotional responses because of their stimulation of lower brain regions. We practiced synchronizing our breathing and pace with that of our partner when rocking them. This synchronizing made exercises much smoother and more relaxing.

Those of us who had active and unintegrated reflexes experienced improvements following just brief practice, though it may take several months to fully inhibit a strongly retained reflex.

I was not surprised to see that many of the exercises were familiar to yoga and tai chi. I had also encountered similar movements through different subject teachers at Rudolf Steiner College when it was a Waldorf teacher training center. Remedial work done in Waldorf schools uses very similar gestures (Spacial Dynamics® or Extra-Lesson for example), and draws heavily on the healing nature of rhyt

Rhythm is a fundamental component of Dr. Blomberg’s program: a gentle, relaxed, steady motion stimulates corresponding brain centers. Given that our development from the moment of conception is guided by the biological rhythms of our mother, it’s no surprise that this is a powerful therapeutic element. The curative potential of rhythm is something I’d encountered in the whole Waldorf approach to education already: the teacher takes into account the rhythms of the seasons, the week, the day, the children themselves. Patterned rhythms are built into the lessons, games, form drawings, songs and verses, and exercises done each day. In my work with children who have special needs, rhythmic movement has been a powerful developmental tool.

“Rocking, swinging, and swaying are all excellent rhythmic movements to foster the integration of the primal reflexes, and should be experienced as often as possible by young children; in fact, fundamental movements are valuable at every age.” – Valerie Baadh Garrett

So fundamental is rhythmic movement that our bodies seek it out when we are in crisis: the person in shock who is rocking back and forth is self-soothing; we instinctively rock others in an embrace to comfort them. Healing rituals of numerous cultures involve dancing, rhythmic drumming or chanting.

Rhythm is recommended by Dr. Bruce Perry, PhD., in his ground-breaking treatment of traumatized children. Working with neuro-sequential (from the “bottom” to the “top”) goals, his approach emphasizes predictable rhythms in the child’s routines but he has also prescribed dance and music classes to his patients. His book, The Boy Who Was Raised As A Dog, describes case studies in which patients had to neurologically “go back” to where healthy development was delayed and process there until the brain’s early need is fulfilled. In The Brain That Changes Itself, author and doctor Norman Doidge describes a stroke victim who learns to walk again by returning to creeping and crawling stages first, developing a rhythmic pattern of left and right, rewiring his brain along a path it had already used once before with success. His experiences with the plasticity of the brain even at later ages are inspiring and hopeful.

We come into life joining its rhythm with the steady beat of our hearts and breathing: that is the baseline for our well-being.

Rhythmic Movement Training has deepened my respect for each stage of reflex development, but also the benefit of smooth, patterned movements for all humans, at all times. In my current role as a resource specialist, I often work with teens whose retained reflexes are apparent in their bodies and behaviors. When I moved from a kindergarten to a high school special ed classroom, I brought in “big kid” rocking chairs. Initially joked about as “old man" chairs, they quickly became a favorite seating option. And not just with students, but my colleagues as well - especially after a rough day! Whatever stage or state you find yourself in these days, I strongly encourage you to “rock on” and “rock out!”

— Kathy Fraser

After teaching 15 years at a small, off-grid mountain school in California, Kathy Fraser is now working at the local public senior/junior high school as an education specialist, where she sees “a LOT of retained reflexes” and has no colleagues with any training in that area. She is making herself known to the one Occupational Therapist (OT) in the district with the intention of getting a screening protocol implemented for the students.

Upcoming Workshop

On Saturday, October 30, the renowned early childhood center Sophia’s Hearth is hosting an online program about retained reflexes. This is a rare opportunity for parents, educators, and therapists to see and work with the reflex movements. Highly recommended!

Thank you for reading The Movement Academy. Please join the conversation by leaving a comment.

Thanks for such a valuable article, Kathy. In my work with young adults with autism, I too found unintegrated reflexes present with almost all students, and that rhythmic work was a key to help open the possibilities for them to progress. Whether it was in dance, drumming, clapping, or the essential routines of activities of daily life, rhythm always seemed to help them feel more at home in their bodies and with the environment. We even worked a project to create and hang large scale swings from the trees overlooking the biodynamic garden fields, and they were a favorite of many, not just because it was fun and a bit risky but because they felt stronger afterward. I'd love to hear how others use subtle rhythmic movement for health and healing. Thoughts?