Thank you all for the many kind comments and emails about the post Movement and the Mountain, and for sharing with me your own resonating experiences with Mt. San Jacinto and the Palm Springs desert. Since I’m a novice writer, feeling my way forward step by step, your responses have given me courage for plowing forward with the new year’s writing. I have more to say about Palm Springs, and will likely do so from time to time.

Yet the hill seems harder to climb lately, and I’m very slow and meandering in my process. Maybe start the trek with a few smaller hills rather than the whole mountain?

First Steps

In the spring of 2016 I was invited to teach a 10 week dance intensive for 12 young adults with autism. A new program called Meristem (inspired by the transformative processes of movement and craft and the Ruskin Mill Trust colleges in the UK*) had just been launched the previous fall, and a full faculty of talented experiential educators had come together seeking to fulfill the program’s vision. That vision imagined a program that could give the students tools for a more independent life and the ability to maintain a job.

I was honored and apprehensive. I didn’t know anything about autism. I had my own style of teaching and didn’t know if it would jive with the students. I would be coming in cold, following a beloved instructor they enjoyed. To check it out, I hopped in my car and drove a couple of hours to Fair Oaks, California to visit a movement class.

I arrived on a warm spring afternoon at the beautiful campus of Rudolf Steiner College. I’d been at teacher training conferences there many times before, both as a participant and eventually an instructor, but I immediately sensed a new vibrancy at work on the campus in its new role as host of Meristem. I was met and warmly welcomed by founding movement instructor AnamCara Bowen, a trained Bothmer gymnast from the UK who had previously taught at Ruskin Mill. She escorted me into the always stunning Stegmann Hall, and twelve pairs of curious eyes turned to me as I was introduced as a friend of the program. Then they turned away and I was mostly ignored in favor of the fun and truly exceptional class that unfolded over the next hour.

Mostly ignored, but not completely, as one at a time curious students wandered over to chat with me and check me out.

Despite my ignorance and preconceptions of how autism might manifest, it was clear that these students loved to move! AnamCara had carefully crafted a robust program of group and partner activities favoring circus skills. The students had been diligently practising movement activities with rods, balls, scarves, and pins for many weeks to prepare for an upcoming presentation. Delighted and encouraged by what I observed, I said yes to the project, and started the dance course a few weeks later.

It’s true that no two autistic individuals are alike, but in reflection I observed that, as a group, there was a bit of stiffness, at times a lack of harmony and organization in the quality of some of the movements. AnamCara and the students had developed a vocabulary of movement together that allowed them to work well and in concert with each other. What, I wondered, could be a key to further unlocking more freedom in movement?

The Music

I quickly discovered what worked best to engage these young adults — music! Each seemed to have their own relationship to different tunes and genres. For some, this affinity seemed fixed on pieces they knew from past programs; others had an ability to survey far and wide into vernacular music from around the world. I discovered that even the most recalcitrant students could be engaged, perhaps in a private setting rather than in the group, with the music of their favorite singer, or with show tunes (often a favorite).

Music seems to fill a space with a substance that invites and welcomes movement, that creates a pulse the human heart and body can follow. The pleasure derived from moving in community with others is itself a reward to experience again and again. Thus, the will to enter the process is engaged, and development can progress.

The Movement

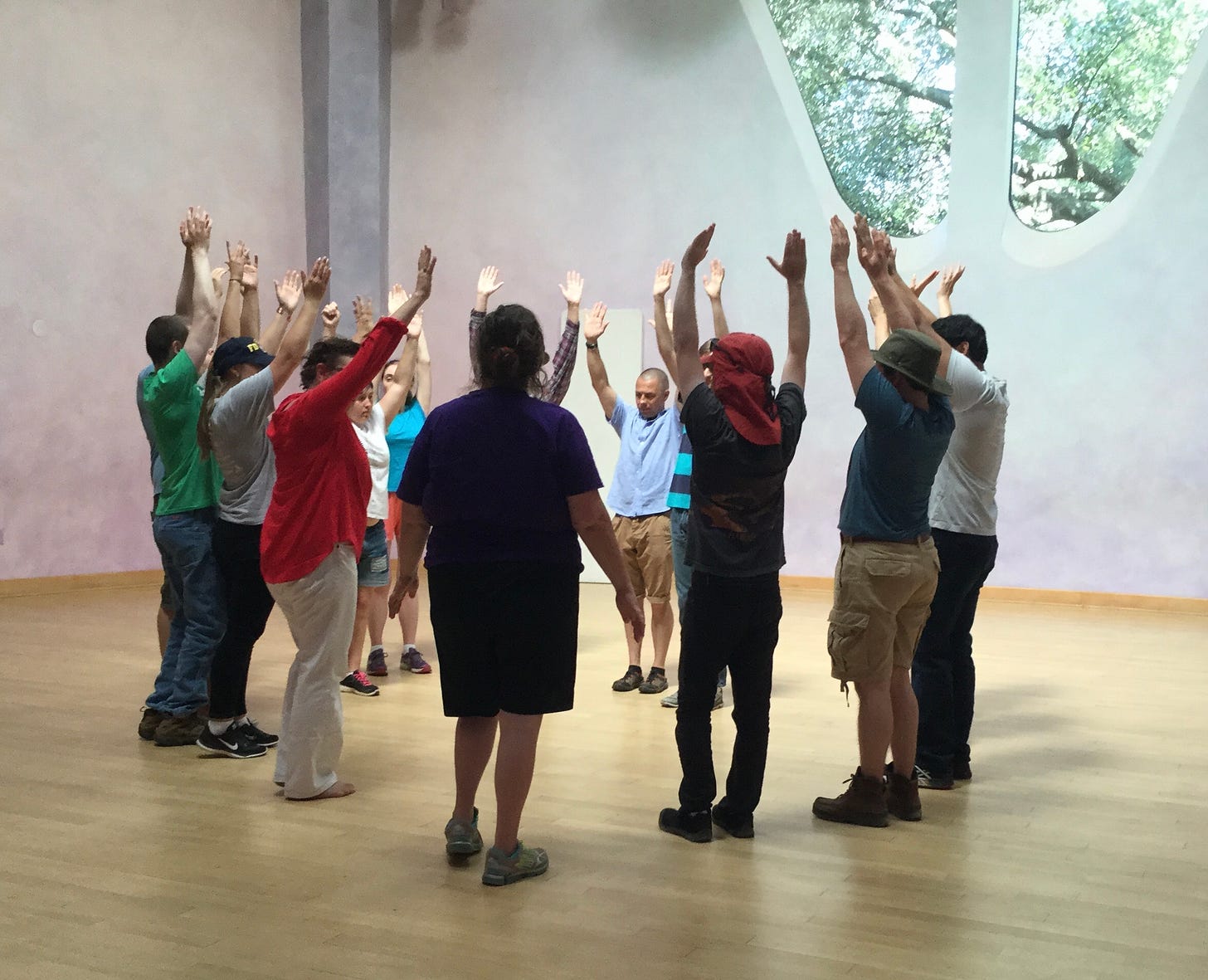

I could write chapters about each aspect of the next weeks. Not only what we did, but about my methods and the movement research behind each activity. We opened and closed each class the same way, with The Rhythm. They’d done this group exercise of expansion and contraction in unison with AnamCara many times and its continuity helped with the transition to a new teacher.

What was especially successful towards a dance experience was walking in rhythm with a partner to Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean, mirroring a partner to Put a Lid on It by Squirrel Nut Zippers, circling and spiraling as a group to King of the Fairies, and swaying together in a group circle waltz mixer to The Lovers Waltz by Jay Unger & Molly Mason. We eventually performed the circle dances at the year’s end commencement to an appreciative crowd of Meristem founders, families, and friends.

At the end these invigorating ten weeks, I was happy to say “yes!” to an invitation to continue working in the program as a faculty member. Over the next few years, working with this and subsequent groups of students, the dance and wider movement curriculum evolved and expanded with essential guidance from founder Maureen Turtletaub, the Transformational Movement Education* (TME) program, and committed colleagues Justin Ganz, Erin Schirm and others. My classes and private sessions also evolved with the theme Body Awareness, and continued to be underscored with music.

The students were introduced to ritual dances (Abbots Bromley, sword dances), creative movement and improvisation, meditative dances, ragtime and swing dances in group forms, circle dances, ethnic dances, and student choreographies. They taught each other, and brought movement into the community with festivals such as May Day, and in programs for youth and elders as well.

Takeaways

I don’t mean to say that I discovered, in music and dance, a magic wand that could be waved to alleviate the challenges of neurologically diverse individuals. Rather, music seems to fill a space with a substance that invites and welcomes movement, that creates a pulse the human heart and body can follow. The pleasure derived from moving in community with others is itself a reward that can be experienced again and again. Thus, the will to enter the process is engaged, and a person’s development can progress.

Next Steps

The research and application of movement principles with people with autism is still in its early stages. Primitive movement patterns, one of my interests, are now being explored. Work at Meristem and in other programs point to positive outcomes for engagement, self-esteem, and motor development from fundamental movement patterns towards mature freedom of movement that can be applied in all aspects of daily life, work, and relationships. Dance certainly has a role.

Check out this new research: Motor Skills in Autism: A Missed Opportunity

*Transformative Movement Education, founded by MAPT in the US, and Practical Skills Therapeutic Education, founded by The Ruskin Mill Trust in the UK

I’d love to hear about your experiences, and to tell you more about the research, successes, and challenges of movement and autism. Interested?

I’d have to say you were my primary movement teacher and in some respects the only one I’ve ever had. You taught me (us) how to use movement to express something specific. To remove the cerebral an insert essentially everything else. I’m always fascinated by how you and Justin and Erin move. I’m grateful I got to feel your walk above the ground when we visited your college. You prove that you don’t need to be an “expert in autism” to be essential towards helping those with autism and those without autism grow.

I agree on so many of your observations. The movement and the love of music somehow makes something work for these young people. Personally, my son,Christopher developed awareness while working with you . Thank you for this article